This

question is asked by Sinclair Davidson over at

The New Zealand Institute. Davidson writes,

Privatisation provides an interesting case study for free-marketeers. Almost everyone is opposed to the notion, yet those same people often buy the stock. So what is it about privatisation that everyone hates?

There are at least three arguments why voters may dislike privatisation. First, there is Bryan Caplan’s voter bias argument. Caplan has argued that voters suffer from four sources of bias – an anti-market bias, an anti-foreign bias, a make work bias, and a pessimism bias. Privatisation as a policy hits all them. Government using markets to sell assets to foreigners who will lay off workers? That couldn’t possibly work.

Then there is Thomas Sowell’s conflict of visions. Privatisation as a policy goes to the very core of the political debate. What is the appropriate role and function of the state in civil society and in the economy?

For those of us who suspect the answer to that question is ‘minimal, at best’, privatisation is an uncontroversial policy. For others not so much.

The thing to remember is that elite opinion holds that the state can and should do more, not less. This remains the case 30 years on from the Thatcher, Reagan, Douglas, and Hawke-Keating eras.

State ownership has many plausible theoretical arguments to support it. The theoretical arguments for privatisation seems weak. It is the empirical evidence that supports the principle of privatisation for many people. But without a clear theoretical basis for the policy, we run into the third problem that privatisation policy faces.

Ok up to this point. What I don't get is why he says that the theoretical base for privatisation is weak when there is a, albeit, relatively recent - post-1990 - literature that provides a solid theoretical base for privatisation. See below. Now I admit its not the kind of material that your average bloke in street is going to read sitting up in bed of a Sunday morning, but the job of the economist then is to make this bloke sit up and take notice.

As to what the theory of privatisation is let us start by noting that there is a surprising overlap between the theory of the firm and the theory of privatisation. The theory of the firm gives us a framework for the theory of privatisation. Hart (2003: C69) makes this clear when he writes,

"Let me begin by discussing the very close parallel between the theory of the firm and the theory of privatisation. In the vertical integration literature one considers two firms, A and B. A might be a car manufacturer and B might supply car-body parts. Suppose that there is some reason for A and B to have a long-term relationship (e.g., A or B must make a relationship-specific investment). Then there are two principal ways in which this relationship can be conducted. A and B can have an arms-length contract, but remain as independent firms; or A and B can merge and carry out the transaction within a single firm. The analogous question in the privatisation literature is the following. Suppose A represents the government and B represents a firm supplying the government or society with some service. B could be an electricity company (supplying consumers) or a prison (incarcerating criminals). Then again, there are two principal ways in which this relationship can be conducted. A and B can have a contract, with B remaining as a private firm, or the government can buy (nationalise) B".

and

"[ ... ] the issues of vertical integration and privatisation have much more in common than not. Both are concerned with whether it is better to regulate a relationship via an arms-length contract or via a transfer of ownership". Hart (2003: C70)

The incomplete contracting framework gives an approach which can be utilised to study the difference between public and private ownership. In fact incomplete contracts are a necessary condition to explain the differences between the two forms of ownership. In a world of complete or comprehensive contracts there is no difference between private and state owned firms. In both cases the government can write a contract with the firm that will anticipate all future contingencies - it will detail the managers' compensation, the pricing policy of the firm, how changes in technology will the change the firm's products etc - and thus the outcome under both forms of ownership will be the same.

This intuition has been formalised into a series of what are called Neutrality Theorems. These theorems formally establish the conditions under which private or public ownership of productive assets is irrelevant for the final allocation of resources. In short they show the conditions under which ownership of the firm does not matter.

Of all the assumptions on which the neutrality results hinge the most important requirement is, as noted above, that complete contingent long-term contracts can be written and enforced. But writing complete contracts is only possible in a world of zero transaction costs. In a positive transaction costs world only incomplete contracts can be written but contractual incompleteness creates a role for ownership - making decisions under conditions not covered in the contract. It is only within such an environment that we can explain why privatisation matters, that is, why the behaviour of state owned and private companies differ.

These neutrality results also show why the previous, roughly pre-1990, theoretical privatisation literature was largely unsuccessful. That literature took a `complete' or `comprehensive' contracting perspective, in which any imperfections present in contracts arose solely because of moral hazard or asymmetric information. But as Hart (2003: C70) notes

"[ ... ] if the only imperfections in are those arising from moral hazard or asymmetric information, organisational form - including ownership and firm boundaries - does not matter: an owner has no special power or rights since everything is specified in an initial contract (at least among the things that can ever be specified). In contrast, ownership does matter when contracts are incomplete: the owner of an asset or firm can then make all decisions concerning the asset or firm that are not included in an initial contract (the owner has 'residual control rights').

Applying this insight to the privatisation context yields the conclusion that in a complete contracting world the government does not need to own a firm to control its behaviour: any goals - economic or otherwise - can be achieved via a detailed initial contract. However, if contracts are incomplete, as they are in practice, there is a case for the government to own an electricity company or prison since ownership gives the government special powers in the form of residual control rights".

Thus privatisation matters only in an incomplete contracts world. In such an environment the allocation of residual control rights will differ and so the behaviour of publicly owned firms will differ from that of privately owned firms and thus ownership and therefore privatisation will become meaningful. This is the basic approach taken in the post-1990 literature.

Schmidt (1996a) considers a monopolistic firm that producers a public good in a world of incomplete contracts. (Schmidt (1996a) is variant of Schmidt (1996b). 1996b considers the case of privatisation to an employee manager while 1996a applies to the case of privatisation to an owner-manager. While this second case is less realistic it is simpler and does not require the assumption that the manager is an empire builder that is utilised in 1996b.) His model is multiple period with the privatisation decision being made in the initial period. That is, the government must decide whether to sell the SOE to a private owner-manager or keep it in state hands and hire a professional manager to run it. Importantly knowledge concerning the firm's cost is private information known only by the firm's owner. Given this, privatisation amounts to a transfer of private information from the government to the private owner. In the next period the manager selects his effort level and the state of the world is then revealed. The importance of the manager's effort level is that it affects the probability of the state of the world. A high level of effort from the manager results in productive efficiency being enhanced and costs being lowered for any level of output. In the last period, the government selects the transfer scheme and payoffs are revealed.

When the firm is an SOE the government observes the firm's realised cost function and thus can implement the first-best allocation by choosing the ex post efficient level of production. But the manager's wage will be fixed, since contingent contracts can not be written, and thus independent of level of output. Given this the manager has no incentive to exert effort and the government knowing this will therefore offer him only his reservation wage.

On the other hand when the firm is in private hands the government does no know the exact cost structure of the firm. In an effort to get the private owner to produce the efficient level of output the government must provide an incentive via the payment of an informational rent.But if transfer are costly it will be impossible to implement the optimal allocation and therefore the cost to private ownership is an inefficiently low level of production. However given the rent payment provides an incentive to increase effort, productive efficiency is greater.

Schmidt's main conclusion is therefore that when the monopolistic firm produces a good or service which provides a social benefit, there is a trade-off between allocative and productive efficiency that needs to be considered when deciding if a firm is to be privatised. The equilibrium production level is socially suboptimal but the incentive for better management results in cost savings. Considered overall the welfare effect of privatisation should be positive for cases where the social benefits are small, but social welfare will be greater under public ownership for those cases where production exhibits large social benefits.

An important implication of this is that a case can be made for privatisation even when the government is a fully benevolent dictator who wishes to maximise social welfare. Even if all the deficiencies of the political system could be remedied it is still possible for privatisation to be superior to state ownership.

In the Laffont and Tirole (1991) model a firm is assumed to be producing a public good with a technology that requires investment by the firm's manager. In the case of a public firm this investment can be diverted by the government to serve social ends. For example, the return on investment in a network could be reduced by the government if it were to allow ex post access to the general population. Such an action may be socially optimal but would expropriate part of the firm's investment. A rational expectation of such an expropriation would reduce the incentives of a public firm's manager to make the required investment. For a private firm, the manager's incentives to invest are better given that both the firm's owners and the manager are interested in profit maximisation. The cost of private ownership is that the firm must deal with two masters who have conflicting objectives: shareholders wish to maximise profits while the government purses economic efficiency. Both groups have incomplete knowledge about the firm's cost structure and have to offer incentive schemes to induce the manager to act in accordance with their interests. Obviously the game here is a multi-principal game which dilutes the incentives and yields low-powered managerial incentive schemes and low managerial rents. Each principal fails internalise the effects of contracting on the other principal and provides socially too few incentives to the firm's management. The added incentive for the managers of a private firm to invest is countered by the low powered managerial incentive schemes that the private firm's managers face. The net effect of these two insights is ambiguous with regard to the relative cost efficiency of the public and private firms. Laffont and Tirole can not identify conditions under which privatisation is better than state ownership.

Shapiro and Willig (1990) consider a world in which there is a public-spirited social planner or framer who decides on the nationalisation/privatisation outcome and sets up the governance structure for the enterprise chosen. The framer's decision is driven by the informational differences between private and public ownership. The important pieces of information are: (i) information about external social benefits generated by the firm; (ii) information concerning the difference between the ``public interest" and the private agenda of the regulator; (iii) information about the firm's profit level (cost and demand information). In this paper there is also a regulator who sets the regulations that control the private firm and who pursues a different agenda from the framer.

Assume that either information about profitability is known before investment is decided upon or that there are costs to raising public funds. In these cases the neutrality results mentioned above don't hold. The equilibrium behaviour of the minister who is in charge of the firm is virtually unconstrained and he will set the activity levels of the firm as to maximise his utility. The regulator of the private firm has a more complex problem to deal with. This involves the designing of regulatory scheme which ensures non-negative profits for the firm. Given this is a case of optimal regulation under asymmetric information we would expect to see the firm enjoying informational rent, which are proportional to the activity chosen. As public funds are costly to raise these transfers are costly to the state.

The trade-off in this model is driven by how easily the public official can interfere with the operations of the firm. If the public official's objectives are the same of the (welfare maximising) framer, i.e. the public official has not private agenda, then public ownership is optimal. In this case private ownership reduces performance since the firm extracts a positive information rent. But when there is a private agenda then a reduction in discretion may increase welfare. Politicians find it easier to distort the operations of a firm in their favour when that firm is an SOE and under the direct control of the minister. The regulated private firms does earn a positive rent but is less subject to the control of the regulator. This means that regulated private firms are likely to out perform SOEs in poorly functioning political systems,which are open to abuse by the minister, and where the private information about the profitability of the firm is less significant. This makes it easier for the regulator to get the firm to maximise social welfare.

In Boycko, Shleifer and Vishny (1996) information problems do not explain the difference between public and private firms. Here it is differences in the costs to a politician of interfering in the activities of the different types of firms that explains the effects of privatisation. The starting point of the paper is the observation that public firms are inefficient because they address objectives of politicians rather than maximise efficiency. One common objective for a politician is employment. Maintaining employment helps the politician maintain his power base. In their model Boycko, Shleifer and Vishny assume a spending politician, who controls a public firm, forces it to spend too much on employment. The politician does not fully internalise the cost of the profits foregone by the Treasury and by the private shareholders that the firm might have.

Boycko, Shleifer and Vishny argue privatisation can be a strategy to reduce this inefficiency in state-owned enterprises. By privatisation they mean the reallocation of control rights over employment from politicians to a firm's managers and the reallocation of income rights to the firm's managers and private owners. The spending politician will still want to maintain employment and can use government subsidies to `buy' excess employment at the private firm. In this model the advantage of privatisation is that it increases the political costs to maintaining excess employment. It is less costly for the politician to spend the profits of the state-owned firm on labour without remitting them to the Treasury than it is to generate new subsidies for a privatised firm. Given that voters will be unaware of the potential profits that a state firm is wasting on hiring excess labour they are less likely to object than they are to the use of taxes, which they know they are paying, to subsidise a private firm not to restructure. This difference between the political costs of foregone profits of state firms and of subsidies to private firms is the channel through which privatisation works in this paper.

Shleifer and Vishny (1994) is a continuation of research stated in Boycko, Shleifer and Vishny (1996). As with the 1996 paper Shleifer and Vishny assume that there is a relationship between politicians and firm mangers that is governed by incomplete contracts and thus ownership becomes critical in determining resource allocation. As noted above the Shleifer and Vishny model is a game between the public, the politicians and the firm managers. The model derives the implications of bargaining between politicians and managers over what the firms will do. A particular focus is on the role of transfers between the private and state sectors including subsidies to firms and bribes to politicians.

To consider the determinants of privatisation and nationalisation Shleifer and Vishny utilise what they term a "decency constraint" which says that the government cannot openly subsidise a profitable firm. To do so would be seen as politicians enriching their friends. The first, obvious, point made is that politicians are always better off when they have control rights. Control brings political benefits, via excess employment, and bribes, to allow a reduction in the excess employment. Both the Treasury and the politicians prefer nationalisation. (Remember that as a SOE the Treasury has income rights and the politician has control rights.) to subsidising a money-losing private firm. Control brings bribes and even without bribes politicians get a higher level of employment and lower subsidies when they have control. The Treasury likes the smaller subsidies that come with nationalisation. When it comes to profitable firms politicians like control or Treasury ownership because these firms have a strong incentive to restructure since the profits go to the private owners and they lose little in terms of subsides due to the decency constraint. To ensure the firms achieve political objectives politicians need control. Given the decency constraint politicians don't want managers who have control rights to also have large income rights since the decency constraint means smaller subsidies are lost if employment is cut and income rights mean the managers gain from restructuring and maximising profits. Politicians who have control prefer higher private and lower Treasury ownership since higher private ownership implies higher bribes. Without bribes the private surplus is extracted via higher levels of employment.

Given that politicians like control, Why would they ever privatise a firm? To explain privatisation the interests of taxpayers must become more prominent. Given this the decision to privatise then becomes the outcome of competition between politicians who benefit from government spending (and bribes) and politicians who benefit from low taxes and support from taxpayers. We would expect privatisation to take place when political benefits of public control are low, and the desire of the Treasury to limit subsidies is high. This is most likely to occur when the political costs of raising taxes to pay subsides is high and when the political benefits from excess employment are low.

The final paper to be considered is Hart, Shleifer and Vishny (1997). Again in this paper information problems are not the driving force of the analysis of contracting out. The provider of a service, either public or private, can invest his time in improving the quality of the service or reducing the cost of the service. The important assumption is that investments in cost reduction have negative effects on quality. Investments are non-contractible ex ante. For the case where the provider is a government employee he must obtain approval from the government to implement any innovation he has created. Given that the government has residual rights the employee will gain only a fraction of return on his investment. This gives him weak incentives to innovate. If the service provider in an independent contractor, i.e. the service has been contracted out, then he will have stronger incentives to both cut costs and improve quality. This is because he keeps the returns to his investment. The downside to private provision is that the incentives to cut costs are strong and the provider does not fully internalise the negative effects on quality of the reductions in cost. With public provision the incentive for excessive cost cutting are reduced as are the incentive for innovation and quality improvements. Costs are always lower under private ownership but quality may be higher or lower under a private owner. Hart, Shleifer and Vishny argue that the case for public provision is generally stronger when (i) non-contractible cost reductions have large deleterious effects on quality; (ii) quality innovations are unimportant; (iii) corruption in government procurement is a severe problem. On the other hand their argument suggests that the case for privatisation is stronger when (i) quality-reducing cost reductions can be controlled through contract or competition; (ii) quality innovations are important; (iii) patronage and powerful unions are a severe problem inside the government.

So arguing that the theoretical basis for privatisation is weak is, I would argue, wrong and the job of any economist arguing for privatisation is to explain this theory to the public, no matter how difficult that may seem.The theory is there and if you want to argue for privatisation you need to find a way of making it intelligible to the general public.

Davidson continues,

The promoter’s problem suggests that you can’t always trust the person trying to sell you something. Given that voters have such poor opinions of politicians, this might be especially true for a privatisation policy. It is easy to believe that past privatisations may have been successful, but that is no guarantee that future privatisations will be.

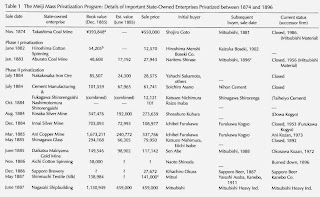

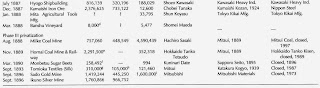

To be sure, not all privatisations are successful and some can be described as having failed after the fact. But the rate of failure is lower for all firms.

For an example of a not so successful privatisations one only has to look at the first large scale privatisation programme in Chile in the mid-1970s. Luder (1991) writes in his abstract,

Between 1974 and 1989, the Chilean government privatized 550 state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Before 1974, all but a handful of major corporations were SOEs. About 50 of the largest enterprises privatized during the 1970s fell into government hands again, only to be re-privatized later. This was due partly to the economic and financial crisis affecting most Latin American countries during the early 1980s but also was a consequence of the privatization modes used. This paper analyzes that unique privatization experience so as to extract policy lessons. The analysis focuses on economic conditions, objectives of government policy, privatization modes, and the divestiture effects on employment, fiscal revenues, public sector wealth, spread of own- ership, and capital market development. (Emphasis added)

In the text Luders writes,

Between 1974 and 1990, the Chilean government privatized about 550 enterprises under public sector control. These included all but a handful of the country's largest corporations. Moreover, the reversal during the early 1980s of the most important divestitures carried out during the first round of privatizations (1974-1978) allowed the government to apply different modes of divestiture during the second round (1985-1989).

and

Consequently, the government intervened in 16 financial institutions. It liquidated a few of them and put in a sound position and re-privatized the remainder. That is, the government, which did not legally own the financial institutions, assumed complete control of a high proportion of the assets it had privatized during the 1970s. These financial institutions included the main commercial banks, whose owners controlled the major pension fund administrators (AFP) and large commercial and industrial enterprises. Because intervention blurred the ownership relationship of these enterprises—i.e., they neither belonged to the public sector nor were owned by the private sector—this group of enterprises was called the "odd sector." Re-privatizing these enterprises as well as other traditional SOEs constituted the second large privatization effort that the military regime carried out.

In short, when privatisation goes wrong, it really can go wrong! Much of the 1970s privatisations had to be redone in the 1980s because they didn't get it right the first time.

Davidson ends by saying,

To my mind, privatisation is always a good thing. But there is a sting in the tail. Very often the proceeds of privatisation are used to buy down debt – in other words, validate past irresponsible government spending. The capacity for debt and deficit is unlimited while the stock of government assets that can be sold off is limited.

The challenge is to embed privatisation schemes into a broader reform agenda.

He is right here, a consistent well thought out reform package is needed. In particular sound market regulation must be in place so that the markets that the SOEs are privatised into are as competitive as possible. Markets have to be opened to competitors before the SOEs are privatised so that the (former)SOE has no incentive to lobby for slow and cautious market liberalisation or better still no liberalisation at all.

This does raise the issue of whether the current government's idea of a partial privatisation of some SOEs is a well thought out reform package. I would say no.

If you look at the economics literature you will also find that fully private companies outperform mixed ownership firms. Some insight on this is offered by a recent paper in the

Scottish Journal of Political Economy (Volume 59, Issue 1, pages 1–27, February 2012). The paper "What Drives the Operating Performance of Privatised Firms?" by Laura Cabeza García and Silvia Gómez Ansón argues that the greater the amount of privatisation the better the performance of the firm. Not an entirely surprising result as the full force of market discipline can only be applied if the firm is fully in private hands but it is something for the government to keep in mind. It would suggest that any performance improvements due to the government's partial privatisation plans will be modest. The abstract reads,

Using a panel data analysis of Spanish privatised firms, we study how different factors influence the operating performance of divested companies. The results show that it is not privatisation per se but other factors that matter. After controlling for possible sample selection bias related to government timing of divestments, we find that the greater the relinquishment of State control and the smaller the percentage of ownership held by managers and/or employees, the better the firms’ post-privatisation performance. Moreover, privatisations that are accompanied by liberalisation programmes and occur during buoyant economic cycles turn out to be more successful. (Emphasis added)

When you look at the performance of mixed ownership firms they don't do as well as fully privately owned firms. For example, Aidan Vinning and Anthony Boardman in "Ownership and Performance in Competitive Environments: A Comparison of the Performance of Private, Mixed, and State-Owned Enterprises",

Journal of Law and Economics vol. XXXII (April 1989) conclude

'The results provide evidence that after controlling for a wide variety of factors, large industrial MEs [mixed enterprises] and SOEs perform substantially worse than similar PCs [private corporations].'

So fully private firms out-perform mixed ownership firms.

Why might the government's idea not work? Simply put there are 6 reasons I can think of:

- First, selling only 49% of the shares in the companies is unlikely to make a huge difference to the way the SOEs are run. In particular the sell off will not make the firms any more efficient since the government will still be the controlling shareholder.

- Second, if the government really does want to maximise the income it gets from the sales selling 49% is not a good idea. 51% is worth a lot more than 49%, that is people will pay a premium for control.

- Third, selling to "Mums and Dads" will do nothing for the amount of money raised, since Mums and Dads will need a discount to make them buy shares.

- Fourth, selling to "Mums and Dads" will do nothing for the efficiency effect of having private owners, since there will be too many "Mums and Dads" for them to be able to coordinate their effects to effect the firm's behaviour.

- Fifth, given that each "Mum or Dad" will own only a very small share of any of the firms, they have little incentive to become informed on the firm's activities since they will only capture a very small amount of any improvement in performance they could bring about. This is another reason why performance is unlikely to change.

- Sixth, the discipline of bankruptcy or takeover is not greater since the government is still the controlling shareholder and is unlikely to let either of these options happen.

Note to self, write shorter posts from now on!

Refs:

- Boycko, Maxim, Andrei Shleifer and Robert W. Vishny (1996). `A Theory of Privatisation', The Economic Journal, 106 no. 435 March: 309-19.

- Hart, Oliver D. (2003). `Incomplete Contracts and Public Ownership: Remarks, and an Application to Public-Private Partnerships', The Economic Journal, 113 No. 486 Conference Papers March: C69-C76.

- Hart, Oliver D., Andrei Shleifer and Robert W. Vishny (1997). `The Proper Scope of Government: Theory and an Application to Prisons', Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(4) November: 1127-61.

- Laffont, Jean-Jacques and Jean Tirole (1991). `Privatization and Incentives', Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization, 7 (Special Issue) [Papers from the Conference on the New Science of Organization, January 1991]: 84-105.

- Luders, Rolf J. (1991). `Massive Divestiture and Privatization: Lessons from Chile'. Contemporary Economic Policy, 9(4) October: 1-19.

- Schmidt, Klaus (1996a). `Incomplete Contracts and Privatization', European Economic Review, 40(3-5): 569-79.

- Schmidt, Klaus (1996b). `The Costs and Benefits of Privatization: An Incomplete Contracts Approach', The Journal of Law, Economics & Organization, 12(1): 1-24.

- Shapiro, Carl and Robert D. Willig (1990). `Economic Rationales for Privatization in Industrial and Developing Countries'. In Ezra N. Suleiman and John Waterbury, (eds.), The Political Economy of Public-Sector Reform and Privatization, Boulder: Westview Press.

- Shleifer, Andrei and Robert W. Vishny (1994). `Politicians and Firms', Quarterly Journal of Economics, 109(4) November: 995-1025.